IDEAS

Coaching heavy, coaching light: How to deepen professional practice

By Joellen Killion

Categories: Coaching, Continuous improvementAugust 2024

In 2008, I introduced the concepts of coaching heavy and coaching light as a way to think about the depth and impact of coaching practice (Killion, 2008). When I first wrote about this, the terms heavy and light were often misunderstood. Some readers perceived that heavy coaching is critical, directive, and even abrasive, while light coaching might be frivolous.

The confusion continued because coaching heavy and light can appear similar in practice to an untrained eye and ear because both involve communication strategies such as listening, questioning, paraphrasing, pausing, and positive presuppositions. These misconceptions often interfered with a deeper understanding of the concepts and their application in practice.

In subsequent pieces (Killion, 2009, 2010), I addressed some of the controversial points and clarified the concept, such as emphasizing that the difference comes more from the coaches’ beliefs about coaching and their identity rather than their actions.

Yet while many coaches and supervisors now stress the distinction between coaching heavy and coaching light, there remains some confusion. In essence, the distinction for some remains locked inside how coaching is done rather than in the driving beliefs and intentions of the coach. In this article, I draw on extensive interactions with coaches and supervisors and my own deepened understanding to offer more clarity about how coaches’ beliefs and intended outcomes affect their actions and ultimately their coaching practice.

By exploring the distinction more deeply from the perspectives of beliefs, challenges, and comfort, I hope to encourage coaches and their supervisors to examine the distinction between coaching heavy and coaching light and their impact on clients.

👥 Coaching heavy connotes a greater level of effort, leading to more significant impact. ''Coaching heavy is about facing what is overwhelming and scary and daunting–and also meaningful and impactful.'' -@jpkillion Share on XWhat these terms mean

Let me begin by saying what coaching heavy and coaching light are not. They are not equivalent to directive and facilitative coaching, approaches described by my colleague Jim Knight. Nor are they about being harsh versus soft or about correcting ineffective practices versus ignoring them, as some have assumed. Others have incorrectly assumed that coaching heavy is more mentoring or consulting than coaching.

I use the terms heavy and light because they emphasize the weight, seriousness, and significance of each type of coaching. Heavy connotes that a greater level of effort is required by both the coach and client and also that this type of coaching leads to more significant impact. Coaching heavy is about facing what is overwhelming and scary and daunting — and also meaningful and impactful.

The work instructional coaches do when they are coaching heavy in schools is about students’ academic and social-emotional and physical well-being. It is about students succeeding in school to contribute to their future potential beyond school. It is also about educators’ well-being and their engagement in reaching their full potential as professionals within an environment that values learning and continuous improvement.

In contrast, coaching light is less about the client needs and more about the coach needs. I find that, when coaching light, coaches are often driven by unacknowledged or unrealized intentions to be perceived as experts or as rescuers. In their drive to be liked and appreciated by their clients, coaches fail to challenge clients, believe in their professional capacity or potential, or allow them to manifest agency in their work. Clients may end up becoming perceived or real victims who are being rescued or even persecuted by a coach. This dynamic creates a subconscious force leading to resistance to coaching.

Coaching heavy may have a greater effect on student learning and teaching practices because it moves the work of coaching into the professional realm of continuous growth. When coaching is light, it can be perceived as frivolous or not useful because it doesn’t tackle the challenges and dilemmas teachers face in their classrooms. Teachers may perceive that they are going through the motions, even serving the coach more than the other way around.

In my first article about this topic (Killion, 2008), I shared that some coaches preferred the terms coaching shallow and coaching deep. I appreciated their choice of alternate words to soften the impact of heavy and light and invoke a swimming metaphor. In shallow water, I explained, both the coach and teacher feel safe. They can touch bottom. But they have a limited perspective of what it means to swim because they can still stand. They are experiencing neither the stress nor the rewards of being in open water.

In deep water, however, both the coach and the teacher are out of their comfort zone since they must depend on their swimming skills to be safe (unless they are experienced and highly competent “swimmers”). Depending on their skills, they may experience anxiety or even fear. This dissonance requires novice swimmers to pay closer attention to their decisions and lean into coaching to gain the expertise to swim. Coaches can alleviate their clients’ fear with temporary flotation devices while they remind clients of their training, reinforce their belief that they can swim, help them navigate their fears, and celebrate with them the feeling of being safe in the water.

How beliefs impact coaching

The distinction between coaching heavy and light is rooted in coaches’ intentions and beliefs as well as their willingness to step out of their comfort zone. Digging deeply to identify existing beliefs, examining them, and adjusting them as necessary is hard work, yet the rewards are boundless.

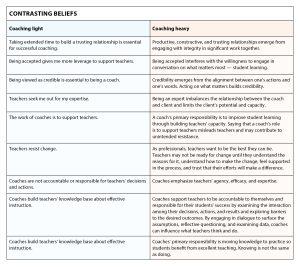

Some beliefs interfere with coaches’ capability to coach heavy, holding them firmly in a coaching light space, unknowingly or knowingly, and therefore limiting the potential impact of their coaching. The list of contrasting beliefs above illustrates how coaches’ beliefs can have side effects that influence coaching and its results.

When a coach’s beliefs are centered more on the left side, the resulting coaching is lighter. For example, if a coach shows up as an expert in a conversation, she is driven by the belief that she deeply understands the context and has the solutions to the presenting problem.

With this assumption, the coach moves into the role of a consultant with a list of you shoulds. The teacher has limited opportunity to engage in cognitive struggle, explore the situation and its impact on the presenting problem, consider a wide range of options available, and engage in the process of making decisions — hallmarks of coaching heavy.

What the coach believes, how the coach shows up in the conversation, what the conversation is about, and the level and depth of the teacher’s cognitive engagement determine the heaviness of the coaching interaction.

Beliefs are not immutable, of course, and neither are coaching practices. But making the shift from coaching light to coaching heavy requires first that coaches examine their own mental models about who they are as coaches, the expectations of their coaching program and supervisors, and the expectations of their clients.

In some cases, coaches are caught between conflicting expectations and beliefs of others and themselves. The list of contrasting beliefs can help coaches assess their own beliefs and serve as a reference point for the coach and coaching program supervisors to unpack the beliefs and expectations they hold about coaching.

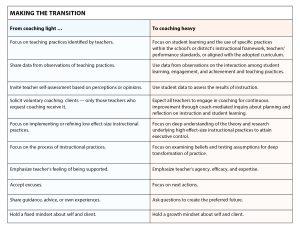

Once coaches’ beliefs are aligned with coaching heavy, they can transition their practice by focusing on content and using the practices, described in the table above, associated with coaching heavy. It is important to note that coaches can use some of these practices while coaching light, yet they will have less impact if the root beliefs driving the actions are not aligned.

Mixing comfort and challenge

Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi (1990) wrote about flow, a mental state in which an individual is fully immersed in an activity, focused to the point of being unaware of outside distractions, and deriving satisfaction from their engagement. For many people, flow is when they do their best and most fulfilling work.

Flow is facilitated by situations in which one’s level of skill and degree of challenge are balanced so that the work seems significant and doable. When the work is too challenging, those without appropriate skills may not persist or believe they can find a way forward. When the work is too easy, it loses its significance, and those engaged may not find it valuable.

When coaches help teachers experience a state of flow, coaching can have a deep impact and facilitate clients’ thinking to recognize their ability to achieve results and realize their potential. Coaching heavy is more conducive to flow than coaching light. In coaching heavy, teachers feel a sense of challenge and are supported to develop efficacy and agency to address the challenges they face through an inquiry lens. Conversely, when teachers perceive their interactions with coaches as light, they may perceive them as time-consuming, not valuable, or not worth the effort.

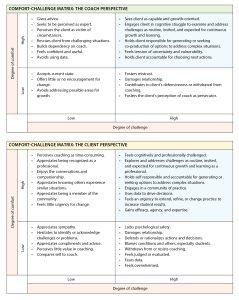

The tables on p. 66 depict the interaction between comfort and challenge from both the coach’s and client’s perspectives. When the degree of comfort and challenge for both the coach and client are high (the shaded top right quadrants of the tables), coaching heavy is occurring and the client has the greatest potential to benefit from coaching.

When coaching heavy, coaches develop a relationship with their clients by engaging in challenging work, acknowledging the complexity of teaching, and cultivating self-efficacy and agency in their clients. They let go of the need to be the expert, are willing to take risks to engage in uncomfortable interactions, and encourage and share vulnerability.

They believe, as do their clients, that the answers to the most complex questions about teaching and learning are worth the effort to discover. As Michael Bungay Stanier states, “We unlock our greatness by working on the hard things. That’s because the hard things break the status quo and break us out of the comfort of our Present Self. Growth means getting a little bent out of shape. And bent into the new shape of Future You” (Stanier, 2024).

Making the choice to coach heavy

To coach heavy means first that coaches examine their own beliefs about the purpose of coaching, how change happens, and the expected results of coaching, then situate these beliefs in the context in which they coach. They are aware of their clients’ beliefs about coaching and explore those beliefs with their clients.

Not all instructional coaching programs expect coaches to promote reflection, metacognition, curiosity, and inquiry as the means to achieve results for students through developing professional expertise, efficacy, and agency. Some expect coaches to work from a technical or expert stance to develop, implement, and even evaluate particular practices that have been adopted for use. In either case, coaches still have the potential to coach heavy or light.

Coaching heavy requires that coaches move to the edge of or beyond their comfort zone and even their competence to model for and invite teachers to acknowledge that vulnerability and uncertainty lead to openness and willingness to refine practice and results. When coaches opt to stay in their own or in teachers’ comfort zone too long, they limit the impact of their work and even waste their precious time and limit the impact of coaching. For some coaches, the thought of this produces tremendous anxiety, hence an openness to what might seem overwhelming and scary to reap rewards and what originally seemed daunting.

The decision to coach heavy or light is the coach’s to make, yet the immediate impacts on the client and their future development are significant. Some might argue that coaching light builds relationships and is appropriate for early coaching interactions. The danger here is establishing a precedent that cannot be easily altered.

Coaching light may also become or be a habit developed over years of practice and, as a result, has become a normative practice and expectation in schools. Yet all habits, even this one, can change with persistence and practice. How a coach coaches affects not only teachers and their instructional practice but also their students and the field of coaching as well.

Download pdf here.

References

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

Killion, J. (2008, May). Are you coaching heavy or light? Teachers Teaching Teachers, 3(8), 1-4. lfstage.xyz/wp-content/uploads/2008/05/are-you-coaching-heavy-or-light.pdf

Killion, J. (2009). Coaches’ roles, responsibilities, and reach. In J. Knight (Ed.), Coaching: Approaches & perspectives(pp. 7-28). Corwin Press.

Killion, J. (2010, December). Reprising coaching heavy and coaching light. Teachers Teaching Teachers, 6(4), 8-9. lfstage.xyz/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/teachers-leading-reprising-coaching.pdf

Stanier, M.B. (2024, March 24). The works with MBS: Unlock your greatness. mbsworks.activehosted.com/index.php?action=social&chash=67e103b0761e60683e83c559be18d40c.784&s=adc10784ee630a1ed9c846b38f576bce

Joellen Killion is a senior advisor to Learning Forward and a sought-after speaker and facilitator who is an expert in linking professional learning and student learning. She has extensive experience in planning, design, implementation, and evaluation of high-quality, standards-based professional learning at the school, system, and state/provincial levels. She is the author of many books including Assessing Impact, Coaching Matters, Taking the Lead, and The Feedback Process. Her latest evaluation articles for The Learning Professional are “7 reasons to evaluate professional learning” and “Is your professional learning working? 8 steps to find out.”

Categories: Coaching, Continuous improvement

Recent Issues

LEARNING TO PIVOT

August 2024

Sometimes new information and situations call for major change. This issue...

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES

June 2024

What does professional learning look like around the world? This issue...

WHERE TECHNOLOGY CAN TAKE US

April 2024

Technology is both a topic and a tool for professional learning. This...

EVALUATING PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

February 2024

How do you know your professional learning is working? This issue digs...